Three friends create video games together. Their love for one another define their lives.

Introduction:

I would consider myself a gamer. I grew up in the 90s and 2000s when video games were a niche activity enjoyed mostly by kids, something that would probably rot my brain, a passion that would eventually fade away as I matured. Spoiler, it did not. My current game of choice when I have a spare minute is Slay the Spire, a simple rouge-like card game released in 2019 with a surprising amount of complexity and depth. I can pull my phone out of my pocket and spend five minutes or forty-five minutes lost within the numbers, randomness, strategy, death, mistakes, sweet victories, and restarts. I find it to be a compact, familiar space in this otherwise chaotic and unknown world. An old friend, one I’ve known for around five years now, called upon as needed when the mood strikes.

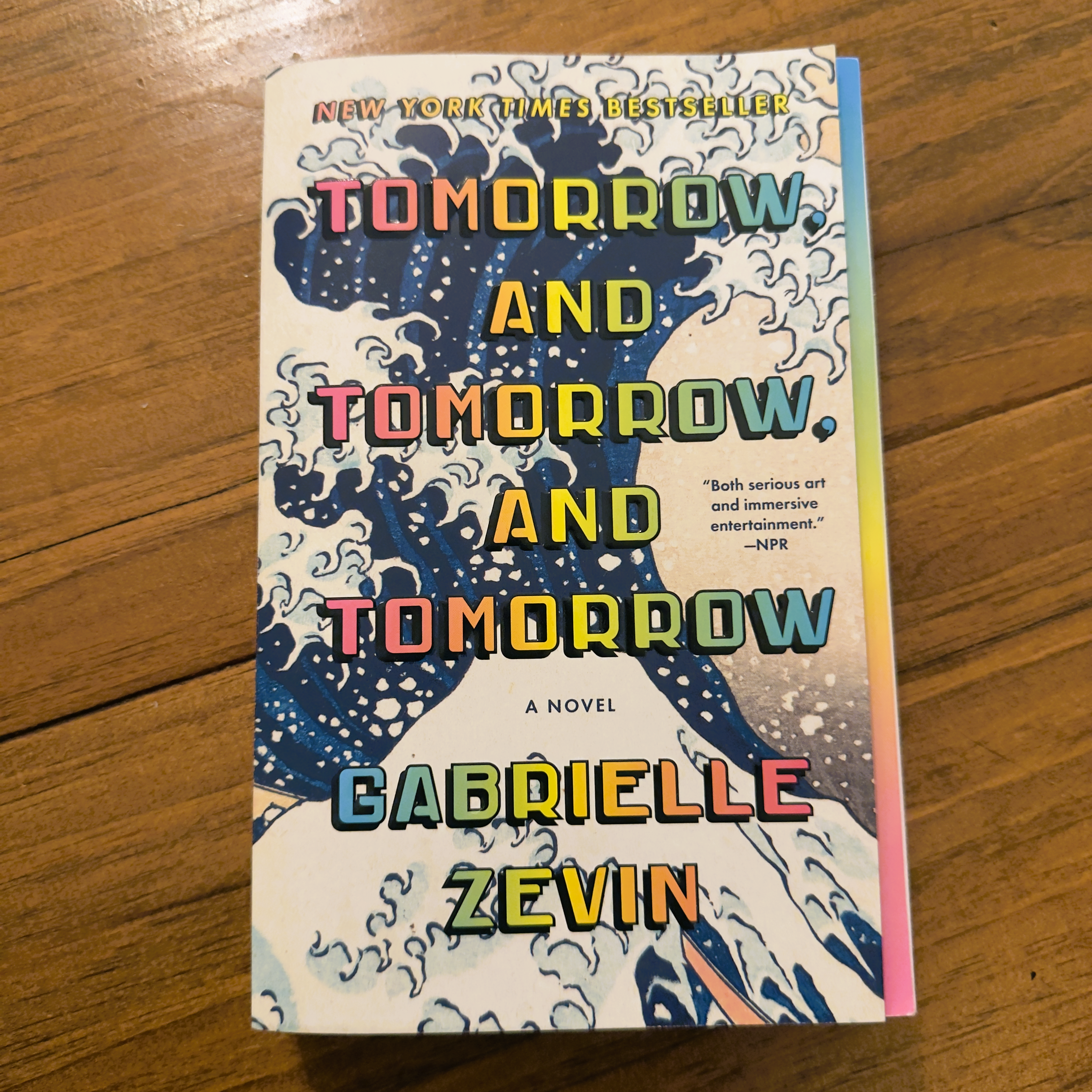

In picking up Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, I did not know that its core idea revolved around a trio making video games. After reading it, I’m torn. Is this book about video games? Yes, it is. That is their work, their job. Is this book purely about that? No. Do you need to know every last reference like I did to enjoy it? No. It’s a book about people, how we create a narrative of our lives, how we change with time, how we grow and fail and try again and break and somehow still survive. Sickness brings new life. Passion can be found everywhere. Best friends stop talking to each other over misunderstandings. Bonds are strained and worked to the limit but are never truly broken.

This book is about what every good book is about. People. And love.

Language (3.5 of 5):

Zevin has a clean writing style with a good grasp on her subject matter, She presents non-fictional topics throughout the narrative to the betterment of the story, such as with her Emily Dickinson quotes or Shakespeare fleshing out the character’s personality or her grasp on programming BASIC. Here and there an oft concept that doesn’t quite land, such as with the section, Pioneers, or her odd soapbox stance on cultural appropriation. Why pinpoint that issue while not having the same pointed emphasis on the other cultural problems in the game industry, like say, sexual harassment? A conscious choice? Did she, on the one hand, want to let the reader decide their take and on the other, need to explain her own stance through Sam’s voice?

Zevin’s use of foreshadowing is impressive, giving the reader a glimpse into where we are heading without bogging down the pace. In contract, I found a rich depth of allusion an opportunity missed, counterplays that could have been highlighted slightly more. For instance, I loved how Sam had a period of depression where he couldn’t come into work, one where Sadie didn’t understand, and later, Sadie found herself in the same struggle. I wanted more light on those rhymes and intermixing of life’s rhythms between the three characters. A tighter weave and more vibrant examination into the art and life that is storytelling.

Idea (4 of 5):

I think it’s a bit funny that video games have gone from a nerd’s activity to the centerpiece of a cultural driven novel. This also doesn’t surprise me at all. We write about farmers, about detectives, about lawyers and doctors and actors and authors. Why not the Makers of Worlds? While the work between these three intertwined souls could be anything, these three characters, Sadie, Sam, and Marx could be nothing more than video game creators. They are fit for the work and the work is fit for them.

Outside of the specific occupation, the book is in essence, about three people. The trickiest and most stabilizing shape and number. Three. Two and you have partners, a bond, a union. Three, and you have fireworks. Front and center is the relationship between Sam and Sadie, the core love story to the narrative. Sideways you have Sam and Marx, the giver and the taker, and Sadie and Marx, the passion for the mind and the passion for the world. Marx plays a supporting role between Sam and Sadie, a stabilizing role. When he is taken out of the picture, the tension and agitation between Sadie and Sam explodes, then whimpers.

Characters (3.5 of 5):

I am conflicted in my view over the characters in Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow. Individually, they are, frankly, not fun people. As a group, as they interact with each other, as they combine and rip apart, they become more than the sum of their parts. I don’t know if I like that fact, the idea that within a community they show more of who they are than who they are alone, or if they are simply deeply flawed people.

Is this good character writing? Or flawed writing? Or exactly what Zevin intended?

Sam, our male protagonist, gets on my nerves. His whole existence is tied around his injury with his foot, how he can avoid the pain, leading to the want to avoid everything. He projects this air of strength in himself, yet we know it’s a façade, a wall to keep people out. This fatal flaw of his is highlighted throughout the story. He makes games to escape the world and to connect with others in a way he can’t emotionally. When the pain and the leg are lost, he doesn’t know how to open up to his best friends, the ones he loves the most and use his weakness to enrich others’ lives. He never learns how to be truly vulnerable.

Sadie, our female protagonist, has her own pain, a mirror in kind to Sam’s. Hers is emotional in nature. She wants so badly to be seen and be known and be loved, yet has no way to grasp it, no way to sink into the joy of the present because she’s always looking for more. A hunger that never ends. She lets others use her, like Dov, because she thinks that will somehow bring her happiness. Injuries to the soul and heart unseen. She lets Sam use her in a completely different way, but so much the same. We see her struggles and mistakes in real time, yet we never see her accept them, learn how to love herself through them, and move on. She builds up these scars as trophies and in the end is left just as broken and in pieces as Sam.

Marx is a ray of sunshine next to these two. Marx is my favorite. He observes, he cares. He loves openly and finds all the wonder in the world. That might be why he does not get as much time within the narrative as the other two, even though he is as crucial to it all as Sam and Sadie. He isn’t interesting in a ‘struggling artist’ sort of way. He knows his way. He’s happy with who he is. Let’s all learn from Marx.

Beyond these three main characters, Zevin writes in a host of well-crafted auxiliary characters. Zoe with her love of the world and her music and her body. Dov with his pretentious attitude and toxic masculinity, the absolutely perfect video game rockstar programmer in the 2000s. Sam’s mom, with her want to create a better life for her son but dies in tragedy. Sam’s grandfather. Marx’s parents, his dad’s disapproval, their gentle love for each other, yet non-legal separation. Alice, Sadie’s sister supporting and disparaging her through the years, Ant and Simon with their gusto and passion through tragedy and triumph and love. The main characters were a bit wanting. Their community filled in the gaps where they lacked. Zevin did a fantastic job with her web of relationships and their history.

Beginning (2.5 of 5):

I’ll be honest, the first hundred or so pages did not grip me. I was at first a bit lost on the time frame of the book, is this the future? The past? Once I understood it to be set in the 1990s, we had some traction. The next question was who were these two, Sam and Sadie? At first they felt like acquaintances, then they were revealed to be bonded through pain. A bond not felt in those first few pages by Sam’s thoughts on seeing Sadie. A bond not uncovered till a few dozen pages later. Was that Sam’s lack of emotional range? Or a purposeful exclusion? I wasn’t a fan. The mix of hinting at the larger picture to be told soon, yet not telling it straight left me confused.

I will forgive any author for their need for time to build-up the characters. We need time to understand how Sam and Sadie are connected by childhood history. We need it to grasp their childish ways. We need it to see how Sadie looks for love and affection and instead finds Dov. We need these pieces laid out for the real work to begin. For us to understand how these two people, partners earlier on in life can become partners again.

Within this early exposition, I could not tell how Marx would fit into all of this. He felt like an auxiliary character all through the intro. The roommate. The suave boy who could interrupt these two friends’ fragile relationship. A danger? A piece of the story’s scenery? No, he’s the man with a huge heart who gives and helps without being asked and never thinks about himself, and in doing so, finds himself everywhere. He facilitates the making of Ichigo from the background, he motivates Sam and Sadie in ways they never would find within themselves. He’s always there, just not actively. His background story doesn’t matter in comparison. He simply is.

I loathe Dov. I identify with Dov. His want to teach and take and lie and not care what others think.

Middle (5 of 5):

The magic in this book happens in the middle. I love how Zevin continues to layer in pieces and experiences and in doing so, creates something truly wonderful. The trifecta creates Ichigo, they have a hit on their hands, and they move to California. How does one go from such a high of success and do it again? How does one find joy in the simpleness of life after their possible life’s high happened so soon in life?

I understand how success breeds resentment. How a lack of communication can cause fissures and uncrossable rifts to form in relationships. Sadie and Sam make me so mad! All it would have taken for them to reconcile is for either of them to somehow bridge the gap to the other. They could speak easily in terms of game development but lacked so much in terms of general honesty and openness. Sadie assumes and assumes and assumes and instead of asking Sam if any of it is true, builds scenarios in her head to blame Sam for which he is innocent. Sam sees these attacks as personal and instead of clarity, defends himself and attacks in return. The cycle spirals and spirals and neither are willing to back down. It’s infuriating!

As the highs of the group’s early twenties churns into the marathon that is adult life, games are made, the company is built, each character finds their lane. Sam sinks into depression and loneliness, dealing with the pain of losing his foot alone. Sadie lets work be her life as she ignores dealing with her issues. Marx supports them both and knows them both.

Then, tragedy strikes.

Character deaths are a tricky thing. You stretch them out and the impact is muted. You cause them to be too sudden and the shock overrides the emotional pain. Zevin writes Marx’s death to a master level. Him being the one who loves life to the fullest, who has the least of it. Him being the glue that holds the group together, now causing them to fly in the cosmos beyond. Him being so much more worthy and deserving of life then either Sam or Sadie. Of course he had to be the one to die.

Marx was my dear friend too. His loss in my life was truly felt.

End (3 of 5):

With Marx out of the picture, Sam and Sadie’s friendship, which started off so strong, had no more glue. No more way to keep them together. Sadie dove deep into depression and pushed everyone away, including Sam. Sam took the pain of losing his two best friends as he did with all pain, alone.

I wish there was more to the ending. Some realization or epiphany, some reason for all the tragedy and hardship to be worth the cost. There isn’t. A friendship falls apart after the death of a loved one and Zevin gives us no silver lining. Life moves on. Sam doesn’t learn how to open up or move past his own shell. Sadie reflects but can’t find the flaws in her own character to find a new path. She returns to the familiar, and life goes on.

My biggest gripe with the ending is Pioneers. It’s such a jarring section to add to wrap up the book. A whole section about an unnamed person playing a game. We have to infer Emily is Sadie and Sam is somehow mixed up in it. There are no context clues beyond it being within this book. I believe Zevin was trying to be artsy, to show the experience of gaming and how loss can be dealt with in activity. To me, it doesn’t add anything to the narrative. How silly experiences in a game can matter where in real life, they make no sense. However, Sam is near stalkerish. Sadie is a victim yet again, this time of emotional bombardment from an unavailable former partner.

A nostalgic Donkey Kong machine doesn’t save the day. A lunch between old friends heals no wounds. There was too much love lost between these two. What could have been a lifelong friendship ended because they were both too stubborn.

What a pity.

Summary (3.5 of 5):

Zevin does many things well. She gives us characters in which we can relate. Sam and his pain, Sadie with her need to succeed. Marx with his love for life. Zevin invests the reader into the characters only to use the twist of the knife and rip one away. The connections and interactions amongst the cast are what make this book special.

However, there are flaws. I didn’t like Sam and Sadie in the end. I could only tolerate them in the beginning. They didn’t grow past their adolescence; they didn’t forgive and find a new path. They didn’t let their failures become lessons for learning. They let tragedy calcify them into their worst features within each other’s lives. Zevin markets this as a love story. At the end, I found no love remaining between Sam and Sadie. I could barely feel it within their most intense moments. Sadie’s resentment for Dov then laid at Sam’s feet undeservingly overshadowed everything else by the time they finished Ichigo. To produce another handful of games with that cloud over both their heads, how could a terribly fragile thing such as love exist?

I read to learn. I read to forget the difficulties of this world. I read to be inspired. Either this book hit me at the wrong time of my life, where it reminded me of my own deep loss too much for me to enjoy, or it was missing something.

Friendships die. No matter how hard you try, or how much you want another person in your life, they die.

If that was Zevin’s goal, to remind us of this bitter truth, she succeeded in spades.